Building Advisory Systems with Intentionality, Equity, Curation, and Impact

Key Points

-

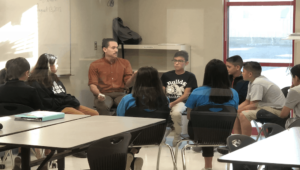

This piece highlights two leaders building advisory systems for today’s students.

-

They demonstrate the intentionality, equity, curation, and impact underscored in the design principles of New Pathways.

By: Bailey Thomson Blake

Seven months ago, I returned to the United States after nearly a decade in Johannesburg, South Africa, where I served as Chief of Schools of SPARK Schools. As I reconnected with friends and former colleagues in American education, I expected them to reinforce the narrative I had consumed while abroad: a crisis of confidence in educators, social media battles over curriculum, and controversial school board meetings. Instead, they were optimistic in their approach to student engagement and skill building and conveyed a renewed commitment to providing students authentic opportunities to grow, achieve, and feel fulfilled.

The Support and Guidance pillar of the New Pathways campaign captures what I heard in conversation after conversation: the desire of instructional leaders, educators, and administrators to respond to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and urgent social movements by emphasizing student agency and belonging. This piece highlights two such leaders building advisory systems for today’s students that demonstrate the intentionality, equity, curation, and impact underscored in the design principles of New Pathways.

I attended the Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School for Government and International Studies in the early aughts. This regional magnet school is known for high student achievement and academic performance. Governor’s School students are often wonderfully weird and nerdy, nurtured by faculty and staff who encourage their quirks and intellectual curiosities. While I thrived at the Governor’s School, I reflect on the experience as an adult and educator with concerns about the emphasis placed on grade point averages, advanced placement, and dual enrollment credits, and SAT scores. This focus has shifted during the tenure of Dr. Robert Lowerre, who has served as Director of the Governor’s School since 2017, and who takes a decidedly different approach to “the numbers.”

Asked about the school’s consistently high national rankings, Dr. Lowerre informed me that, early in his tenure, he was disturbed by the announcements he found hanging throughout the building touting the school’s elite status. “I took down all the posters,” he says. “I didn’t understand the methodology, and I didn’t believe in that foolishness. Those were all outputs.”

Instead, Dr. Lowerre is obsessed with what he calls “welcomeness,” a surprisingly tender term that encompasses his school leadership vision. “You don’t lower standards when you open the door wider,” he proclaims. Dr. Lowerre believes, and the school’s data from the past five years shows, that academic performance need not be divorced from creating a community where students feel accepted and valued, learn and practice cultural competency, and prepare to lead the world of the future.

Dr. Lowerre characterizes the challenges of instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic and the racial reckoning prompted by the murder of George Floyd as a burning platform that fueled rapid evolution in the Governor’s School’s modus operandi. These events were, “an opportunity to make a clean break from the way things had always been done, or at least a new way to look at things,” he states.

You don’t lower standards when you open the door wider.

Dr. Lowerre

This year, the school hired its first full-time mental health professional, a school social worker, who will focus on exceptional education services, mental health, and teaching coping and mindfulness strategies to students. Dr. Lowerre is convening a working group to review and overhaul the school’s required class for freshmen, Foundations of Independent Research and Communications (FIRC), to ensure that the course’s sequencing and content align with the skills that students should have when they graduate. He’s looking into grading practices and course weightings to ensure that students pursue classes and experiences they find enriching, instead of selecting classes based on grade point incentives. And, perhaps most importantly, he’s drawing on his own teaching and leadership experience to interrogate inequity in the school’s admissions, recruitment, and operational practices.

“You have to be willing to stand in front of the mirror naked and make a commitment to change things,” Dr. Lowerre contends. “It would be easy to sit back and do what we’re doing because the output is good, but it’s not good enough. We can do better. Every kid can have a great experience.”

Lauren Harris is the Director of Student Integrity and Community Standards at Agnes Scott College, where I am currently enrolled in a post-baccalaureate program. Following fifteen years of student affairs experience at small and large-tier post-secondary institutions, she joined the university in 2021 to uphold the college’s longest-held tradition, its Honor System. Director Harris’ mission, in service to the Agnes Scott community, is to integrate “cultural humility and restorative practices to advance student development.”

While it may seem counterintuitive to highlight student discipline in the discussion of Support and Guidance, Director Harris’ perspective is illuminating: “In disciplinary work, I get to listen and hold space for students. I see them in their development, hear their rooted concerns, and put support around that. I’m supporting them in their practice to become their best selves.”

Director Harris also sees discipline as an opportunity to intervene through informal and formal resolutions. Intervention allows the administration to understand unmet needs and provide support services to ensure student success, notes Director Harris. In this process, she has “the opportunity to challenge and support students with their assumptions, biases, and values.”

Director Harris believes that institutions commonly misstep when they “do the work in a vacuum without student involvement and input.” As a staff advisor overseeing the college’s student-led Honor Court, Director Harris emphasizes student leadership because “peer influence creates aspiration.”

Agency and contribution

New Pathways emphasizes the primacy of durable skills, defined by Stephanie Short, America Succeeds Vice President of Partnerships, in a recent Getting Smart town hall as “how you use what you know and how you show up in the world.” Short and her team argue that students who are equipped with and exercise durable skills build personal agency and make meaningful contributions to their greater community.

Dr. Lowerre and Director Harris provide a glimpse of durable skill-building in practice in secondary and post-secondary contexts. As they lead Support and Guidance initiatives at their institutions, they demonstrate how commitment to this New Pathways pillar blends high standards with authentic care.

This post is part of our New Pathways campaign sponsored by American Student Assistance® (ASA), Stand Together and the Walton Family Foundation.

Bailey Thomson Blake is the former Chief of Schools at SPARK Schools.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.