How The Principles of Experimentation Can Support Postsecondary Decision-Making

Key Points

-

The principles of experimentation can be applied to research and guidance.

-

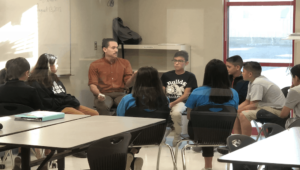

One can facilitate conversations about postsecondary pathways within the classroom, empowering young people to share findings, feelings and hopes about their future.

By: Jared Schwartz

“The College Lab is the single most valuable project I’ve ever completed.”

As a high school AP Chemistry teacher, it’s a powerful statement to hear from a student. It might also seem like an odd project name for a science class. But I discovered years ago that all good chemistry lessons include student exploration and problem-solving–and that isn’t so different from the skills required to create a plan for life after high school.

My classroom has about 90 sophomores, juniors, and seniors who take the class for a variety of reasons. It’s one of many classes they will take at Walter L. Sickles High School, putting them one step closer to the end of the year and graduation. It also means that when a student steps into my classroom, AP Chemistry is just one of many things on their mind.

The reality is that many high school students are feeling unprepared for what comes next. They’re eager for more guidance. It’s why I’m never surprised to hear students look at class curriculums and ask themselves “How will this even help me?”

I wanted to better answer that question so several years ago, I applied the scientific principles and practices of chemistry that I’m familiar with to an equally important topic: Planning for the future.

Bringing College and Career Discovery into the Classroom

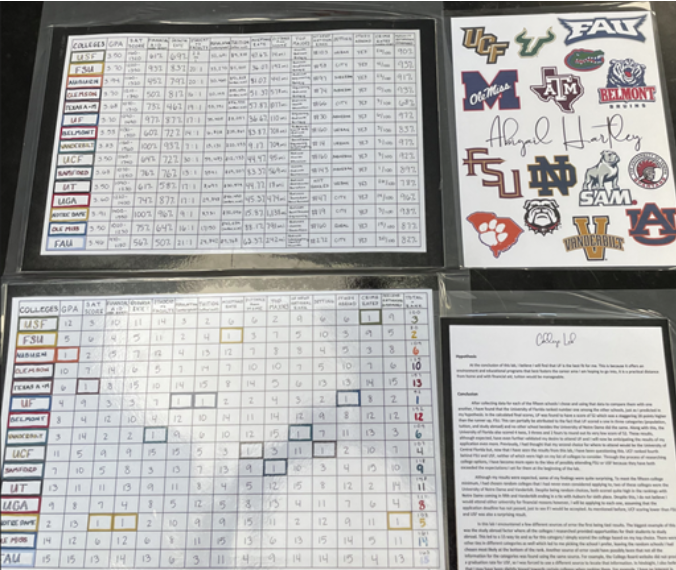

The College Lab is a two-week project I lead that invites college and career conversations into the classroom.

The need is urgent. A Morning Consult survey of 1,200 high school students for College Board looked at students’ attitudes about the future, and while it was encouraging to see that 46% felt motivated about exploring a career, 48% also said they felt anxious. My goal is to spark my students’ interest in these discussions so they feel confident making smart choices about a future career, college planning, and finances.

The project is structured around five scientific principles:

- Conduct Research. Students research 15 diverse schools or majors they might be interested in. Using College Search on BigFuture, students can access profiles for more than 4,000 institutions – spanning certificate, 2-year, and four-year programs.

- Make a Claim. As they research, students form a hypothesis as to which college they believe will be a good fit for them.

- Experiment. Students are given independent time to gather information about each institution according to the criteria that they chose to explore. The free planning site offers career exploration and financial planning resources so during this process, students might discover how a major connects to a potential career path or how they might afford postsecondary education.

- Draw a Conclusion. Based on all of the information gathered, students draw a conclusion as to what school they believe will be the best fit based on the data collected.

- Commentary. Students are given time to discuss the implications of their data and conclusion, including any sources of error, bias, or unexpected results.

As students explore, there is time for peer discussions. This can elevate lines of inquiry that they may not have thought of and spark further dialogue as students begin to discover similarities in their research. Many of my students claim that being able to discuss the project allows them to home in on the most important aspects including majors, campus life and financial aid.

Haley, a former student of mine shared, “I [now] feel like I can make a decision about college that actually makes sense.”

3 Tips for Your Classroom

Students accomplish a lot in the two weeks but dedicating that amount of time isn’t always possible. If teachers are looking for meaningful ways to have a conversation on the future with their students, they can:

- Start Small: Have students start with the college or career quiz on College Board’s BigFuture. The questionnaire can help students connect to key information on the site.

- Give It a Try: Offer a small-scale assignment for students to explore some prospective colleges and universities. Ask for a smaller list or see what they can learn in a shorter amount of time.

- Be a Resource: While we don’t have all of the answers, we can provide our students with support. That may be sharing our own college experience, connections to guidance counselors, and knowledge of free resources that can aid students.

Not every student in my class walks away from the project knowing exactly what they’re going to do or where they’re going to go next. My hope is that 100 percent of my students will finish with a better understanding of their options and what it might take to get there. Regardless of the path they choose, I hope that the decision that they make is one that is informed and puts them in the best position to find success.

Jared Schwartz is an AP Chemistry teacher at Walter L. Sickles High School in Tampa, Florida which serves a diverse population of students. Jared teaches 10th through 12th graders. This is his 11th year teaching, and he couldn’t imagine doing anything else. His goal is to not only provide students with an enjoyable and rigorous learning experience, but also instill values to develop citizens of the world. When he’s not teaching, Jared enjoys running, golfing, reading, and spending quality time with his wife and newborn son, Teddy.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.