Using Schoolwide Design Sprints to Seed Student-Centered Culture

Key Points

-

With a solid process and supportive staff, students can develop the confidence needed to take these skills to be critical thinkers and help solve real-world problems.

-

Read more about how Macon Early College began using the design process as a way to plant the seeds for a more student-centered culture.

By: Gloria Painter and Adam Haigler

“I am so proud of what you students have been able to accomplish with this work and look forward to seeing how you use these projects to make an impact in our community.” This was what Jim Breedlove, the Board Chairman of Macon County Schools (NC) had to say after he and a group of local community members were panelists to hear a set of “pitches” from students at Macon Early College. The students were tasked with using the design process to develop project prototypes for real-world issues that could then translate into project ideas that the school would launch in the 2023/24 school year. This is the story of how that came together.

Schools around the world are increasingly interested in empowering student voices and including them in decision-making around governance, discipline, and curricular direction. There are myriad reasons for this shift, which shows promise in improving engagement, cultural responsiveness, academic, and socioemotional outcomes, especially for traditionally underserved students. Though the interest in these practices continues to grow, many schools overlook the school culture shifts that must occur to create sustained innovation in the mindsets and practices foundational to this philosophy.

Meanwhile, many forward-thinking schools are seeing excellent results from involving their students in the Design Process (for instance, Design 39 and One Stone), a continuous improvement framework that has been used to design countless products and services that are based in deep empathy for the user. In the 2022-23 school year, Macon Early College (MEC), a small high school in Southern Appalachia, began using the design process as a way to plant the seeds for a more student-centered culture. Though the process has not been without setbacks, the overall impact has been remarkable, as there has been a palpable shift in student willingness to engage in solving problems within and beyond the school. It has also led to a new, shared language of design thinking and an authentic feeling by the students that they can indeed have a positive impact in their community.

MEC is located in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina, and was established in 2006 as a part of the New Schools Network, primarily funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Emerging from the isolation of COVID-19, MEC felt a strong need to reconnect with its local community and culture. So, during a faculty meeting at the end of the 2021-2022 school year, the school planned to dig into our area’s rich history by centering its 2022-23 school year focus on Cherokee culture – the tribal nation on whose traditional territory the school resides. This was done by arranging student groups around the Seven Cherokee Clans and empowering students to design meaningful activities around this cultural focus. At the same time, the school wanted to find a way to shift towards hands-on, experiential learning, including Project Based Learning (PBL). The focus on the region’s Cherokee heritage was an obvious choice for a schoolwide theme that would help students delve into local history and contemporary topics. However, as the school year began, the project was plagued with issues that led to a lack of buy-in from students and teachers alike.

Pivoting to Address School Culture

A positive school culture doesn’t just happen in a vacuum. It is designed, built, and maintained by students, faculty, and the community. It is a part of the educational experience that breathes and lives within and outside the school building. MEC’s initial approach with the Cherokee project involved radical student leadership – essentially asking them to guide their groups on how the project would look from the earliest stages. Though some groups were able to thrive in this loose framework, most of the students expressed frustration with the lack of direction and leadership. After a semester of such frustration, the students and staff decided that they would shift their attention to planting the seeds of student leadership throughout the student body so that they might become more capable of supporting such a project in the future. By partnering with Open Way Learning (OWL), the entire school participated in several Design Sprints that have had an intriguing impact, which could be instructive for other schools considering similar aims.

Student voices being heard is significant for them to have ownership in what they need and want, which is critical for building a student-centered culture. Design Sprints gave students the ability to have a safe place to voice concerns about their school and the changes they wanted to make. The student body gathered to dig into the problems they were facing at school before designing solutions. The platform in which OWL provided MEC students grew their confidence and started to build a culture within MEC that students and their voices mattered. The identifiable issues students voiced concerns about were communication, student voice, and clan leadership. Cameron Ramsey, an MEC student commented that, “For me, incorporating design sprints into the educational framework not only amplifies student voices and decision-making, but it also cultivates a sense of ownership, fostering a truly student-centered learning environment where our perspectives and preferences were valued and integrated. That is not the norm right now in most cases, so this experience gave me some hope for a better future in learning and being a student at Macon Early College.”

The lack of timely and clear communication was a significant theme throughout the first session. This was also discussed in School Improvement Team meetings because communication was a goal MEC staff identified needing to work on. For instance, newsletters in previous years were designed, maintained, and sent by the data manager, but this had become overly burdensome for her already full plate. Meanwhile, families and students also expressed interest in the previous school year’s newsletter and asked why they weren’t being issued. Interestingly, a solution for having a student group take charge of the newsletter had emerged during an SIT meeting, but had yet to surface. Other communication issues that surfaced were the student body not feeling prepared for upcoming events such as clan and service days and the lack of general information concerning school happenings. Indeed, the communication between leadership, clan leaders, and their clans was poorly planned or lacked follow-through. Overall, students felt that information concerning service opportunities and general information concerning daily updates or changes in the schedule weren’t being communicated effectively, which was leading to mounting frustration.

As a faculty member, it is hard to hear the things your students are not pleased with. However, as educators, we know that our students are the drivers and their needs matter. MEC had to be open and honest about what our students were voicing. We had to encourage ourselves to give up control and allow our students to guide this change. Our belief is that this will build a school culture that is solid and purposeful.

Promising Results

Since these initial sprints, communication between students and faculty has increased – admittedly with setbacks, but also some key victories. Now, thanks to a group of intrepid students, a weekly flier is sent out with some consistency to the student body, which contains next week’s events and a preview of future events. The students also wanted in-person announcements face to face, which was initially accomplished via Google Meet, then a recorded video. Currently, it has evolved to become face-to-face in our shared space first thing Monday morning. This gives the entire staff time to make personal announcements, add or provide clarification while also allowing the students to ask questions or add comments. Another new emphasis, which was recommended by students, has been the TV screens in the shared space, which continuously present announcements and other important school information. Overall, since our first design sprint meeting, students feel like they have a partnership with their school.

A clear indicator of this has been watching clan leaders starting to meet independently to take ownership of clan days. Clan leaders actually schedule meetings after school to collaborate and plan the assigned clan days, something that never happened previous to the design sprints! To take it one step further, they are now designing Google Forms to give the student body voice and choice in what activities to participate in on Clan days, then communicating with teachers about their plans. The collaboration among leaders is dramatically more effective than it was beforehand. Jackson Kelley, a junior MEC stated, “OWL helped bring out the initiative in many of my fellow classmates. This jumpstarted them into thinking of new ways to alleviate the strain on student events and the miscommunication that came with it. We started having professional meetings and strategically planning on how we wanted the school events to perform. Once we had done this, we all had struck gold. It is among my highest wishes that future MEC students can look back on the work we did and use our strategies to fix their own problems.”

Setting the Stage for Next Year

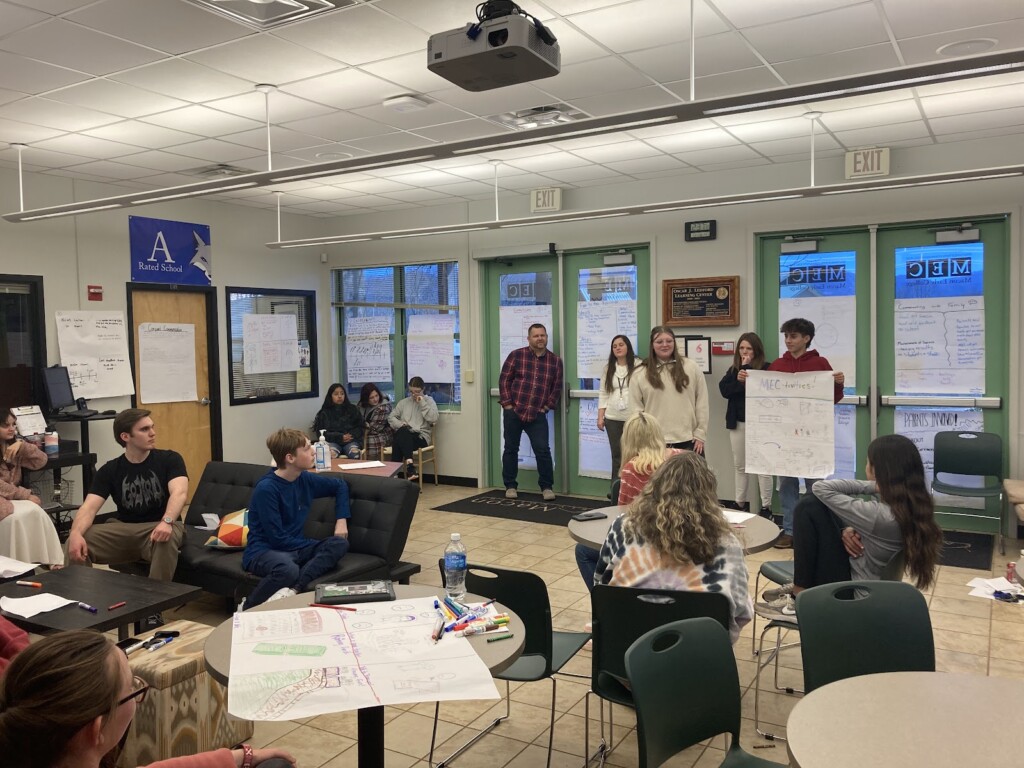

We ended this school year with another Design Sprint that had students choose problems they were interested in solving from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Grand Engineering Challenges, and 100 People Project. The students independently investigated and selected problems of interest, then formed groups based on those interests, developed a problem statement, brainstormed potential solutions, and then prototyped one that they presented at a schoolwide pitch day in front of peers, MEC faculty, and community members. MEC has now gauged student interest in a variety of topics that will be used to create schoolwide projects next year, thus increasing the likelihood of student engagement and buy-in.

Bringing The Process To Your Context

These Design Sprints have centered MEC’s focus and developed a school culture that is already fostering and supporting more powerful Project-Based and student-centered learning. Along the way, MEC’s learning community has discovered that (1) student voice creates a strong school culture, (2) every student can be included, and (3) school faculty and leaders must be open to what students suggest.

It has been inspiring to see how effective it can be to partner with students in creating a school culture. Giving them a framework to not only voice their opinions but develop detailed prototypes of potential solutions, led to highly constructive feedback that has been quickly operationalized by MEC’s team. A pleasant surprise was how the students took ownership of their part of the problems they voiced and subsequently assumed responsibility for the solutions they devised.

Most efforts to embolden student voices involve only a select group of students, like the student council, which almost invariably represents only the most successful and motivated among the student body. This leads to predictable equity issues that could be avoided by involving all students in a Design Sprint process so that all voices can truly be heard in the process.

Finally, without a willing and open staff, none of this would have been possible. We must be cognizant of how deflating it can be to ask students for their ideas, and then disregard them right afterward. Any school that commits to a process like this must also commit to implementing the most promising solutions that emerge. Being transparent about what constitutes a “promising solution” is essential along the way to avoid undermining the fragile trust that is being co-created – an essential element to a student-centered culture.

MEC’s team has learned so much along the way and encourages others to undertake a similar process! It has now become clear that, with a little help from a solid process and supportive staff, students can develop the confidence needed to take these skills to be critical thinkers and help solve real-world problems.

Gloria Painter is an education leader at Macon County Schools, NC, and Adam Haigler is the Co-Founder and chief Operations Officer of Open Way Learning.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.